If we look at our surroundings from a slightly different perspective, most things can be seen as a process of problem solving. From individual daily choices and relationships to the process of organizations establishing visions and designing structures, the countless decisions and attempts we face are ultimately within a flow of defining problems and finding solutions to them. Viewing the world through the lens of problem solving helps us organize vague situations into language and gauge our next choices. This may sound obvious, but the same applies to our own concerns. From the burden of major exams to anxiety about career paths, to questions about what we will do with our lives—when we define these concerns not as vague emotions but as problems to be solved, and reinterpret our experiences as resources for solving those problems, what we already have and what we still lack become relatively clear. This allows us to view what actions we need to take next in a more structured way.

Amidst the somewhat abstract desire to create impact that changes our surroundings, I had been contemplating between entrepreneurship and graduate school. For me, the perspectives on entrepreneurship learned in the Business Venture and Entrepreneurship class and a project I carried out as an extension of that became an opportunity to glimpse, however faintly, 'what problems can be solved through entrepreneurship' and 'how can such problems be addressed in the form of a business.' This article was written to record the thoughts and learnings from that process.

I still don't know a clear methodology for choosing good ideas or items. I wonder if this is even a problem with a correct answer. This project was merely a prototype; it didn't generate revenue or change the world. However, the process of defining problems, setting hypotheses, and seeing how those hypotheses transformed in reality has clearly left a great meaning for me, and I think it's enough if the trajectory of that change can provide even a small insight to someone.

This article will unfold the story following the order in which the project progressed, while organizing the perspectives learned in class from Professor Jong Hoon Bae along the way. The professor played a key role in establishing the Department of Business Administration in Entrepreneurship, and through the class, he made me see entrepreneurship not as 'the skill of creating a company' but as an approach to dealing with problems. This article focuses on problem definition and validation, which are part of market test, one of the two major stages of commercializing ideas (market test and scalability).

Entrepreneurship / What is an Entrepreneur?

Before developing the content, I want to organize how we should view 'entrepreneurship' and 'entrepreneurs (or entrepreneurship studies)' that run through this article. The entrepreneurship that the professor defined in class was a unique attitude toward solving the problems of our time. This definition was impressive because it made me see entrepreneurship not simply as creating a company or a means of generating profit, but as an approach to dealing with problems.

From this perspective, the purpose of entrepreneurship is closer to verifying whether problem solving actually works, rather than profit itself. When the problem we want to solve is accepted by the market, the result appears in the form of profit. Ultimately, entrepreneurship can be said to be the process of redefining problems that already exist around us but were taken for granted, and creating a market that can solve them.

That's why excellent entrepreneurs design a market model before a business model. Rather than thinking about what more to sell to people who are already consuming, they consider why some people haven't become consumers yet, and what needs to change for them to enter the market. The starting point of entrepreneurship is not optimizing existing markets, but discovering points that existing markets have missed.

However, such attempts are inherently uncertain. It's difficult to clearly measure or know at the start how big the problem we're trying to solve is, or whether it can expand into a market. So entrepreneurship is not a choice that can be completed through calculation, but a process where you can only know the result by taking risks and pushing through to the end.

Non-consumer

Entrepreneurs represent non-consumers. The story of Steve Jobs heard in class was very helpful in understanding this perspective. He is known to have distrusted consumer research, but this was closer to believing that the language of people already in the market cannot explain new markets, rather than ignoring consultants' or customers' words and metrics. We can think of what Steve Jobs called customers' "taste" as connected to understanding the characteristics of these non-consumers.

Efficient markets don't leave opportunities idle, so money left on the table disappears immediately. When we view markets as finding inefficiencies that no one has noticed, we can look at entrepreneurship from more diverse perspectives.

What Problem to Solve

So how can we decide what problem to solve? Of course, there's no correct answer here either, but through this project, I've come to view ideas and problems from at least the following two perspectives. In the subsequent content, I'll explore more specifically how these criteria changed the project's direction and what choices were actually made.

- Check the system and infrastructure that constitute the problem.

- First identify the resources and capabilities the team has, and select a problem of a size that can be solved within that scope.

Design Thinking and Infrastructure

Our team also repeated the process of ideation and complete revision for nearly two months, and only in the last month were we able to make relatively rapid progress. That's how arduous the process of exploring 'problems that look good' was. At least the various problems or items we explored included:

- Information gap problems arising from the lack of local news media

- Lack of information accessibility due to insufficient promotion of local communities or campus organizations

- Imbalance in cultural infrastructure concentrated in large cities

- Employment gap for college graduates and concentration of highly educated workforce centered in the Seoul metropolitan area

- Lack of business direction setting and mentoring in the youth entrepreneurship process

- Small-portion vegetable sales targeting single-person households

- Café study space platform for using neighborhood cafés like study spaces

- Subscription management fintech for managing and recommending multiple subscription services

- Consultation and information curation targeting information asymmetry in insurance after traffic accidents

- Entry problem for amateur creators in the music market where consumers and producers are clearly separated

- Response solutions for malicious customers, i.e., 'problem customers'

- Mental health counseling app services dealing with depression or burnout

Most were problems we'd heard about at least once, or that someone had likely already tried. And the characteristics these items commonly shared were also clear: they hadn't been concretized as items yet, had been discussed for too long, and were difficult problems to address. So why do these problems keep appearing but rarely get solved? When we view them from the perspective of infrastructure rather than superstructure, a completely different interpretation of problem definition becomes possible.

An example the professor gave in class helps understand this perspective. The problem of university hierarchy is a social issue that appears periodically in Korea. When approached from superstructure—admission systems, excessive competition, or the success-oriented mindset of the parent generation—the problem always becomes personal, complex and solutions become vague. However, viewing it from infrastructure allows a completely different interpretation. Seoul National University is the school with the largest budget invested per member, where the most resources are concentrated. That's why people flock to Seoul National University. From this perspective, this problem transforms from a B2C problem like individual choice or culture to a B2B problem.

We initially chose and developed a vegetable meal kit for single-person households, but from this perspective, we can anticipate that this too is an item with limitations. Approaching from superstructure, i.e., top-down, centers on psychological narratives like the increase in single-person households, the hassle of cooking, and the desire for a healthy meal. In this case, strategy easily concludes with emotional packaging, storytelling, and warm copy. However, we can easily confirm that such attempts have repeatedly failed. Conversely, viewing from infrastructure, i.e., bottom-up, the problem becomes much clearer. Let's think: the reason single-person households don't cook is not willpower but the difficulty of small-quantity purchases and the inefficiency of storage and disposal. Here, single-portion meal kits inevitably have high costs due to small-quantity production and freshness maintenance, and in B2C marketing structures, customer acquisition costs are also critically high. Ultimately, unless this structure is fundamentally solved, such items are difficult to sustain. In fact, the solutions that have survived are closer to indirect B2B solutions provided in bulk by companies or schools rather than individuals.

Two Approaches to Discovering Customer Value: Design Thinking and Lean Startup

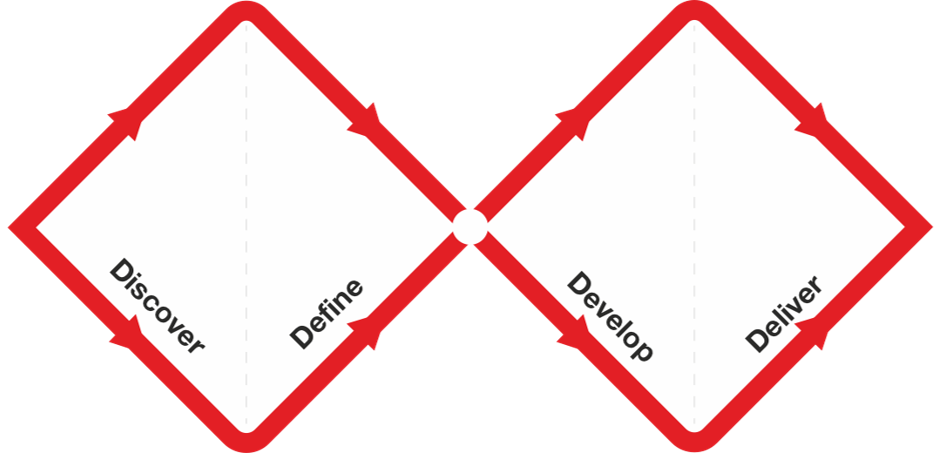

Design thinking is bottom-up, closer to an inductive approach. It explores potential problems through customer interviews, iterates problem definition, and then derives solutions that match, following a problem-to-solution flow. This connects to the infrastructure exploration approach mentioned earlier.

On the other hand, lean startup is top-down, a deductive approach. It's a method often used in tech entrepreneurship where technology or solutions exist first, and problems that can be solved with them are explored, having a solution-to-problem structure. The repeated direction changes in this process are commonly called pivoting.

Again, What Problem to Solve

At the beginning of class, the professor gave several examples of items worth noting at the time from the perspective we've been discussing—exploring problems in areas where inefficiencies occur structurally and haven't been sufficiently addressed.

- Household accounting or fintech: Inefficiencies remaining throughout the payment and settlement process

- Schedule coordination: Communication costs that grow exponentially as more stakeholders are involved

- Collaboration tools, productivity apps: Especially for mid-sized companies, internal processes and system maintenance often lag behind as they focus on growth

- Energy industry: An industry where government regulations strongly apply, but structural transitions and growth are simultaneously occurring

We decided at the end of a meeting to shift direction and look for industries with structural inefficiencies, targeting B2B. Rather than capturing specific problems or ideas, we decided to first find industry groups. The industry groups we reviewed in that process included:

- Apparel (sewing) industry

- Food service industry

- Automotive parts industry

- IT companies

- Campus education centers

- VC

- Healthcare industry

Among these, the sewing industry was what we first began to look into deeply, and this ultimately became the choice that led to our final prototype. Once the direction was clearly set, the subsequent process proceeded very quickly and systematically. Our project ultimately received both votes from participating students and the professor's selection, and looking back, this wouldn't have been easy if we hadn't chosen the sewing industry. I think this was because we ultimately followed the professor's repeatedly emphasized feedback to "find a problem of a size you can solve" and chose the area our team could handle best. I'll discuss the professor's feedback on 'finding a problem of a size you can solve' in more detail in the subsequent process.

There were three main reasons why our team could handle the sewing industry relatively effectively. First, one team member was a fashion & textile student who was studying related content in a professor’s class focused on smart factories, which address structural problems in the sewing industry. Another team member's parents worked as a manager in the industry, so we could directly hear about problems actually experienced in the field and quickly receive realistic feedback on the solutions we were conceiving. Finally, I had spent the previous vacation interning in a lab conducting computer vision research, having acquired both basic theory and hands-on skills to handle it to some extent. As these experiences combined, the sewing industry became not just an 'interesting problem' but a problem our team could push through to the end. This is why I emphasized earlier that accurately identifying the resources and capabilities the team has is important.

Numbers

Although I said earlier that entrepreneurship is difficult to measure quantitatively because it must create new markets, it's still fundamental to find the most similar market and identify the numbers that market values. We must understand market characteristics and establish clear pricing strategies to design sustainable structures.

On Pricing

Demand is heterogeneous. Everyone feels different prices are appropriate, so we must collect data through numerous attempts to find the right price. Can the price of a beer be the same at a neighborhood pub and a hotel lounge in a tourist area? Beyond cost calculation, pricing has an aspect of implicit cognition, i.e., social consensus.

The Starbucks pricing controversy the professor mentioned in class was also a good example for understanding this. While news criticized that prices increased despite falling coffee bean costs, Korea's café cost structure has large variables beyond coffee beans: rent and labor costs. The rise in labor costs and rent had an impact exceeding the fall in coffee bean costs. This also suggests that cafés in Korea could be seen as selling space as much as coffee.

Interestingly, this is also where the structural inefficiency mentioned earlier becomes apparent. What solutions could reduce these costs to lessen the realistic burden on owners?

Finding a Problem of a Size You Can Solve

The subsequent process was a repetition of interviews and feedback. In fact, if we've reached this stage, the subsequent progress will be sufficiently possible somehow. So what's more important is what the professor said: finding a problem of a size the current team can solve—that is, how to find a problem that four college students can solve. Here, I want to briefly organize how we narrowed down this problem.

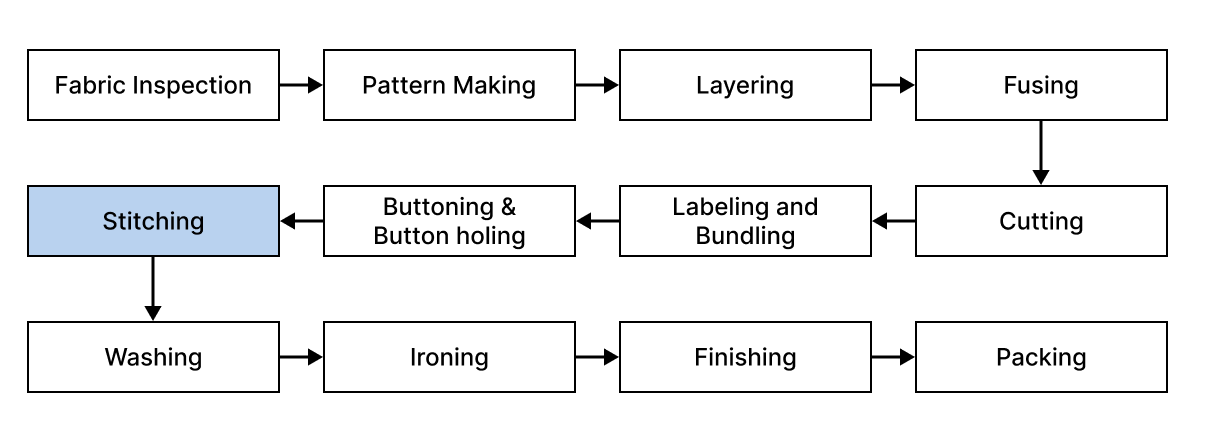

The apparel industry is a very large industry extending from fabric production to cutting and sewing processes, to the final distribution of produced clothing. The problem is where to step within this vast industry. Below is part of the records I organized for team meetings. Through these materials, I could confirm the thought that inefficiencies in sewing factories might be an unsolved problem, and that this problem is deeply connected not just to improving work efficiency but to industrial structural and social problems.

Research Notes (Excerpt)

Sewing Industry Related Article (2014)

Analysis that sewing production unit prices have barely risen in nearly 20 years, stemming from Dongdaemun Market's declining competitiveness and competition structure with overseas low-wage labor. Cost reduction through production and distribution structure utilization was presented as an alternative.

The production unit price of sewing producers in Changsin-dong has barely risen over the past 20 years despite inflation, because Dongdaemun Market's design competitiveness has declined and sewing producers must compete with cheap labor in China or Cambodia. Therefore, to save Changsin-dong's sewing industry and increase Dongdaemun Market's competitiveness, we must improve clothing design and quality while utilizing the close distance between Changsin-dong and Dongdaemun Market to reduce production and distribution costs.

Independent Designer-Factory Connection Service FAAI (2019)

Points out that the production part is the most backward in the fashion industry, and many designers give up production because they can't connect with factories.

"I learned that the most backward part of the fashion industry is production, and I became confident that connecting factory operating systems with designers would create synergy," saying "It was sad to see designers put in a lot of effort to produce clothing but give up because they couldn't connect with production factories."

Fast Fashion and Surplus Fabric Problem (2020)

The sewing industry is also connected to environmental problems. However, personally, I think funding-based recycling models have limitations in scalability.

Sewing Industry Digitalization Related Article (2022)

While distribution is highly advanced, manufacturing sites are fragmented without even standardized work instructions. The aging of skilled workers (50+) and lack of young worker influx are simultaneously pointed out as problems.

While online platforms like Musinsa are growing rapidly and the fashion distribution market is becoming advanced, the apparel manufacturing industry is fragmented without even unified work instructions, let alone digitalization, making individual access even more difficult. Unlike the rapidly changing fashion distribution industry, fashion manufacturing companies have 80% of their workforce, including sewing technicians, over 50. Without standardized work instructions, everything is written and drawn by hand in industry-specific jargon that only industry people can understand.

Conclusion

While researching materials, I could find many attempts at how to personalize and customize, but relatively few materials dealt with what process factories actually work with. However, I also had doubts about whether the aging and workforce discontinuity pointed out as the biggest problems in the sewing industry could be solved by simple efficiency improvements alone.

I decided to look more into inefficiencies in sewing factories and checked additional government reports and research papers. Textile and fashion industry reports presented macro alternatives like automation, smart factories, and expansion of foreign workers, and a survey paper on clothing brand ordering methods relatively well organized the inefficiencies and inconveniences between factories and brands. By checking these contents and cross-validating them through interviews with the professor and industry practitioners, we came to focus on defects occurring in the sewing process, particularly in sewing factories, among the long processes of the apparel industry. Whether clothing is well sewn is difficult to check during the sewing stage, and is mainly checked by skilled workers' visual inspection at the QA stage when finished products come out.

In this way, I was able to dig into the apparel industry that I had no knowledge of and discover one small problem.

Materials on Overall Garment Production Process and Errors in Sewing Process

Material Explaining Overall Garment Production Process (2022)

Can examine what processes exist in large factory garment production.

Research Report on Garment Production Defects (2019)

"From our survey we can clearly say that most of the garment faults occurred in sewing section."

Types and Frequency of Defects Occurring in Sewing Stage

These defects in sewing errors currently mostly depend on skilled workers' visual inspection at the final QA stage, causing significant time and cost inefficiencies, and this content was also confirmed through interviews with the professor.

Once the problem is this specific, we can easily think of clear directions for how to solve it, and likewise can clearly explore past technical attempts or related technologies to solve it.

Technical Feasibility Review

Research Using Latest Computer Vision Technology for Defect Detection (2020)

Research on Defect Detection Occurring in Sewing Process (2022)

A recent paper by Korean researchers, impressive for focusing on sewing defect detection. Beyond technical feasibility, we could also get practical hints needed for prototype implementation, such as using low-resolution cameras.

Now I could see how to address this problem. While changing the entire sewing industry might be impossible, reducing sewing errors in the sewing process on-site is a problem we can sufficiently address. We set our final hypothesis that we could solve the problem by creating a solution that improves this inefficiency and selling it to companies operating sewing factories.

The Story After

The stories that follow are, strictly speaking, somewhat distant from the core this article wants to convey. However, they were a process of verifying whether the problem we defined was actually an implementable problem, so I'll only briefly touch on them.

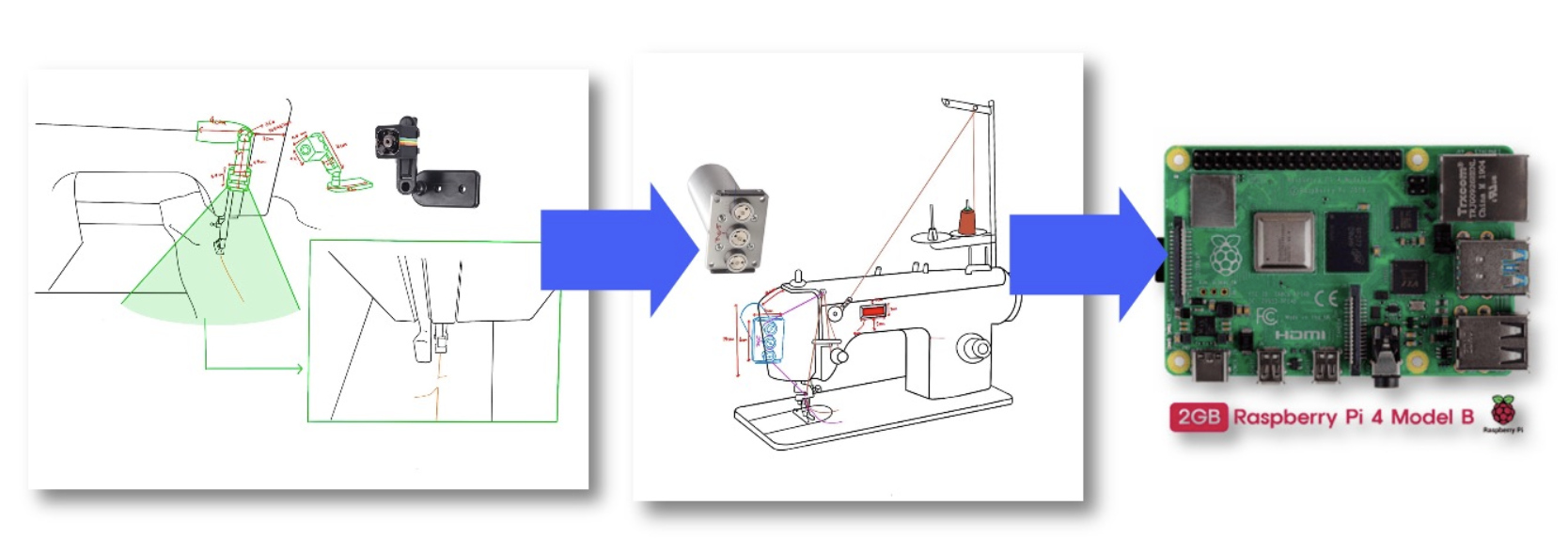

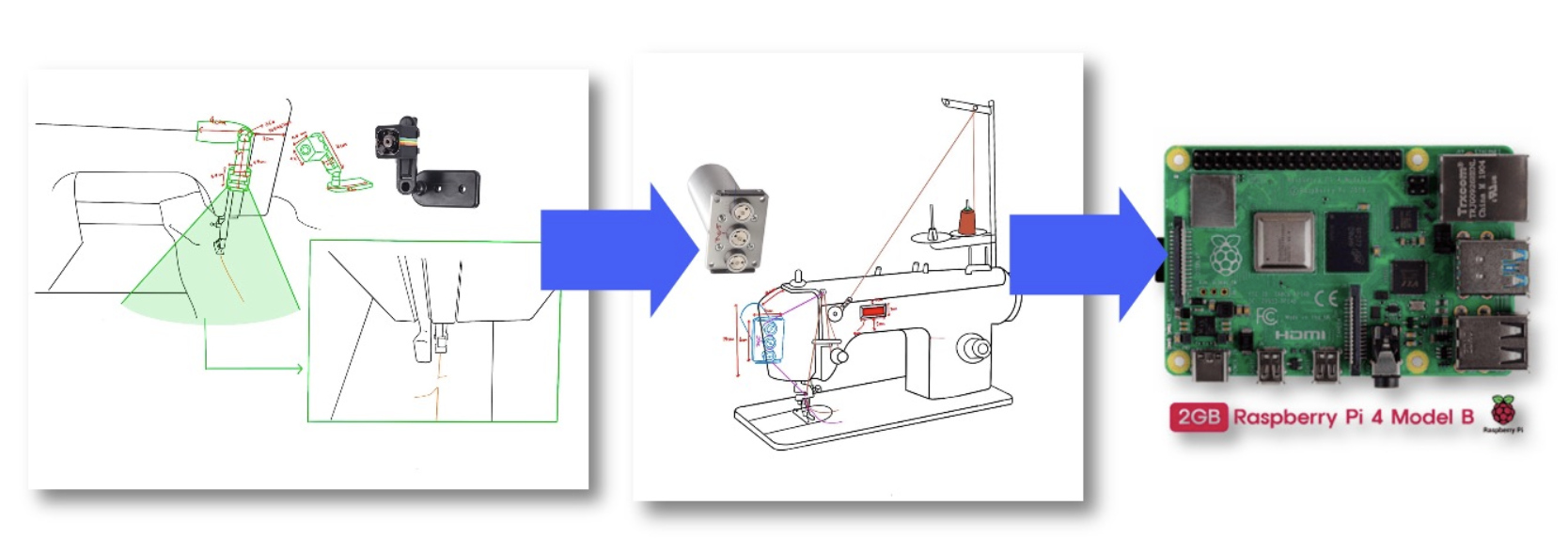

I believed that we needed to detect the results of the sewing process in real-time to give immediate feedback to workers, while also being able to be introduced into existing factory systems without difficulty. Considering these conditions, I judged that an on-device solution directly attached to sewing machines was more suitable than a centralized structure. To this end, I directly constructed a sewing dataset and, based on that data, trained a YOLOv5 model to verify at a prototype level the technical feasibility of detecting sewing errors in real-time.

Additionally, I selected hardware needed for the prototype such as Raspberry Pi modules, accelerators, and camera models, calculated costs, and hypothetically estimated how many sewing machines the solution would need to be introduced to for the profit structure to work, and at what price point we could sell to companies. As a competitive model, I presented Mitsubishi Electric's sewing machines with sewing error detection functions, emphasizing that our solution could be introduced at relatively lower cost and entry barriers since it could be attached to existing sewing machines without replacing specific equipment.

On Marketing

While the perspectives we've confirmed so far are considerations about technology and products, marketing is about directly making customers understand the problems we've identified and teaching them how to consume.

A representative example from class is the concept of space and place from Yi-Fu Tuan's Space and Place, a representative text in human geography. Space refers to space, and Place is formed when human experiences accumulate and memories are created there, giving it meaning.

For more concrete examples, consider two well-known Korean variety shows: 1 Night 2 Days, a travel-format program in which celebrities visit different regions, and Running Man, a game-based show filmed around public locations and new venues. Although viewers may not consciously notice it, 1 Night 2 Days often works as an effective tourism promotion tool through close coordination with local governments. Running Man similarly partners with venue operators, naturally showcasing new buildings and spaces as the cast runs missions through them. That’s also why “Yeosu Night Sea,” a widely recognized Korean song, can make Yeosu feel familiar even if you’ve never visited.

Some Business Models

I've organized the business models the professor taught in one place. The two most basic models are as follows.

1. Focus Model

A method of creating economies of scale by focusing on one industry/function and making that the source of efficiency.

- Representative case: TSMC - Generates profit as a foundry that efficiently handles large-scale mass production.

- Average production costs decrease as production volume increases, with conditions that fixed costs are high and large-scale facility investment is needed, and this is only valid in industries that meet these conditions.

2. Integration Model

A method of generating profit through synergy (scope economy) by directly performing multiple stages of the value chain.

- Representative case: Samsung Electronics - Makes finished products but also makes the parts that go into them, creating synergy effects.

- Such vertical integration carries the risk of losing customers when achieving economies of scale. For example, if Hyundai Motor acquired POSCO, Toyota wouldn't buy steel from POSCO. Nevertheless, this is possible because synergy is created by sharing production facilities, marketing channels, brand power, etc.

Other models are as follows.

3. Coupling / Product Bundling

A method of combining two or more products, designing one for market expansion and another for profit generation.

- Representative cases: Printers don't generate profit, but profit is generated from cartridges that can only be used with that printer. Pubs give a lot of salty and dry snacks so customers buy more expensive beer.

- Possible when selling two or more products where synergy occurs between them, and customers feel greater happiness when buying both. At this time, trying to generate profit from the product that increases market share can seem like betraying customers. This is one of the most commonly adopted methods in actual entrepreneurship.

4. Crowding Model

A model where something being used by many people becomes value itself. Mimetic consumption is key.

- Representative cases: E-commerce, restaurants that deliberately make customers wait in line even when there are seats

- Products that many people are buying lead to purchases without much thought, which is called network effects. Network effects are more likely to occur when consumption behavior is highly visible, products reveal individual identity, and it's difficult to check product quality in advance, only possible through reviews.

- Even at a loss, strategies often focus on growing customer scale in the early stages.

5. Catalyst Model

Platform business. Also aims for network effects, but the difference is a structure where customer acquisition probability increases as the customer base of complementary goods that can be coupled with the product increases.

- Representative case: Smartphones and app ecosystem. As the number of users wanting to use apps installed on smartphones increases, more people use smartphones.

- In Multi-sided Markets where consumer types are too diverse to lower production costs, or where standardized products don't exist so each maker creates different products, it may be difficult to form a platform.

- Another characteristic is that the core of a platform is that the entire ecosystem must grow. Therefore, selling proprietary products on the platform can be risky in the long term.

Other models include:

6. Profit Multiplier Model

Expands margins by attaching additional products and services centered on core business.

- Representative case: IP industry and movies, music, theme parks using it

7. Pyramid Model

A method of preempting future customers by simultaneously operating high-end and low-end industries.

- Representative case: The reason Mercedes makes the unprofitable A-Class is that even though it doesn't make money immediately, it familiarizes people with the Mercedes brand while securing initial customers to capture potential consumer markets.

8. Time Profit Model

A strategy suitable for industries with short product life cycles, often considered by startups.

- Representative case: Fashion industry - Leading trends one step ahead, and when trends enter maturity, launching new different products using a hit & run strategy.

- Since the time to create barriers isn't long, planning ability is more important than mass production capability, and ways to reduce the risk of someone copying are needed.

9. Blockbuster Profit Model

A strategy of recovering multiple failures with one big success.

- Representative case: VC

- Since the cost of investing in one product isn't large, costs of launching one are reduced, and marketing costs to deliver to customers are more important.

10. ERRC / Blue Ocean Strategy

A framing that aims for a monopoly market by escaping perfect competition markets.

- Representative case: Budget hotels - Remove restaurants, don't worry about architecture, make rooms small, remove reception. Instead, focus only on clean beds and rooms so this can be delivered to customers at low prices.

- Answer these questions: Among various elements, what is unnecessary? What can minimize service levels? Among various attributes, what can increase quality compared to competitors? What completely new things can we try?

Conclusion

I'll conclude the article with stories the professor shared at the end of the semester.

When talking about the AI Revolution, technology cannot be left out, but what's as important as technology trends is how we understand the lives of people who interact with it. This is important regardless of whether you're in humanities or sciences. People's lives are very different from textbooks, and different from the world seen while studying in Seoul National University. The world is much wider, more complex, and has more reversals than we think. If we miss this complexity, it's difficult to grow into a meaningful entrepreneur. Because we are agents and proxy entrepreneurs of our time solving not our own problems but someone else's problems, we must ultimately think about these things.

Also, there are numerous businesses behind the stage, not on stage. It's about innovating the process—that is, processes and collaboration methods—through which things are made, rather than the results themselves. Solving such problems actually creates more opportunities. Collaboration tools are representative examples. When we say that Korea's labor productivity is lower than Germany, Japan, and the US, the most likely cause can also be found in inefficiencies accumulated throughout the entire production process rather than individual capabilities.

One last thing, entrepreneurship is a life of being the servant, not the master. It's not a life of being a boss and living comfortably, but closer to a life of a performer who constantly thinks to solve others' problems. Managers are not people who abuse power, but people who solve problems on behalf of customers.

Entrepreneurship is not persuading (the market) but being chosen (by the market). Rather than trying to calculate what will be chosen, we must remember the following three things.

- Respect the market. Everyone is as rational as I am, and moves within incentives that make them act that way. If we design products without understanding this, we easily go astray.

- Present your own perspective independently.

- And wait for that choice.

2 and 3 may seem somewhat paradoxical, but whether the problem I'm solving is right is ultimately something only the market can know. My answer to the world's problems is thrown one-sidedly toward the world, and it only leads to business success when there's a response. If you find interest in the process of asking this question and waiting for its answer itself, then entrepreneurship itself can be a sufficiently attractive journey.